You don't need to 'glow up'

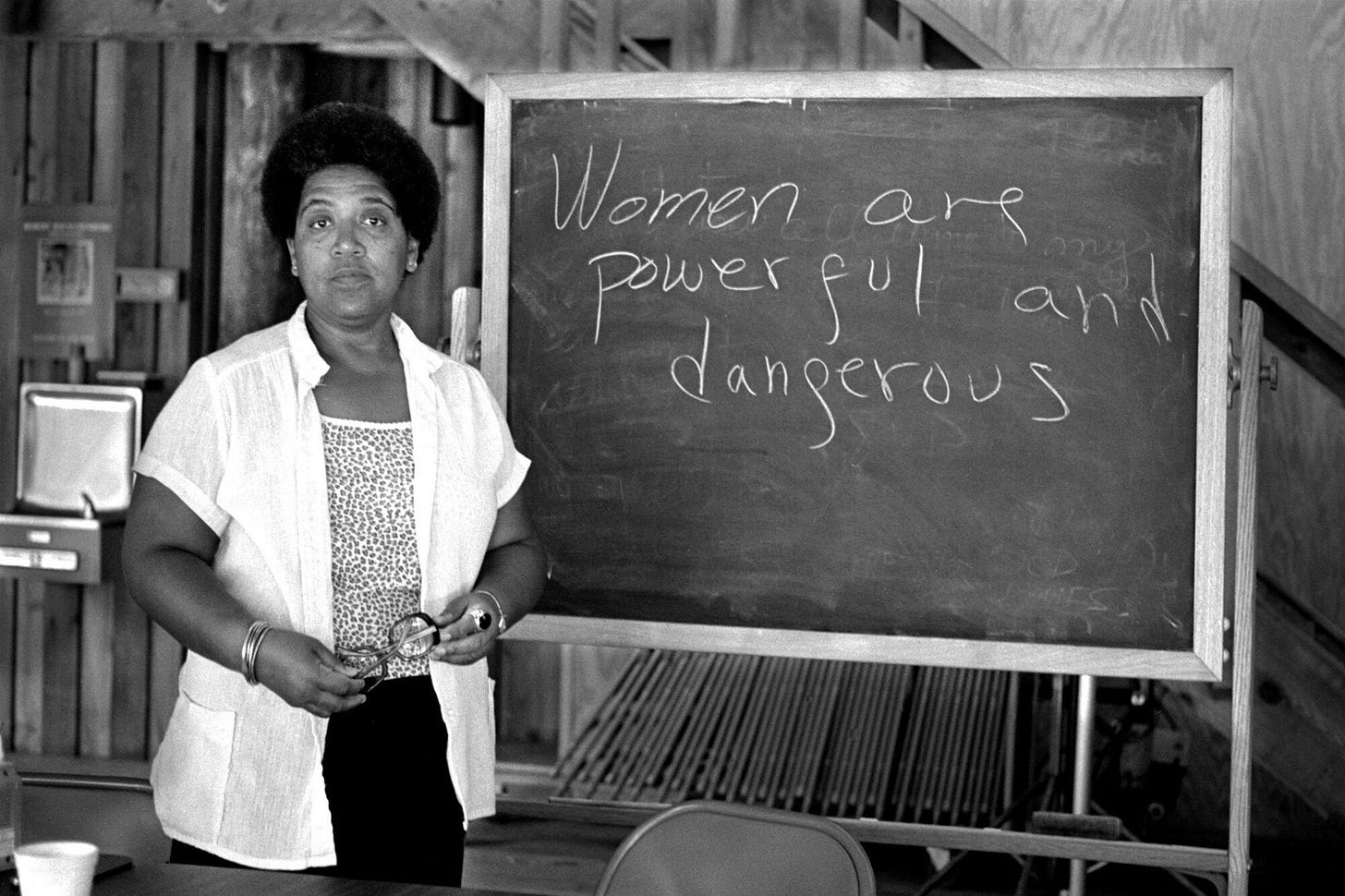

As Audre Lorde said: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.”

I hope you’re enjoying It’s Not That Bad, a newsletter by Chloe Laws. This is a fully reader-funded publication, if you like it and can support it, please sign up for a paid subscription. Love you 4eva!

This week, I shared a poem on my Instagram called ‘notes on coming back to yourself.’ In it, I wrote the line: “No, you don’t need to glow up / you are not fairy lights strung enthusiastically upon a Christmas tree.”

I have been ruminating about how much ‘glow ups’ have permeated society and how far we’ve come from the true meaning of self-care for years now. When I first heard the term ‘glow up,’ it felt fun and light-hearted, as these social media trends often do. Then, as predicted, it malformed into something uncomfortable. In its essence, a glow up has always been a capitalistic, misogynistic practice. They have always been laden with Eurocentric beauty ideals that push us to be the thinnest, whitest, most feminine versions of ourselves.

Glowing up has become synonymous with self-care on social media platforms (particularly TikTok). Influencers show us how to glow up, combining aesthetic pursuits (Gua Sha nightly; wear these snatching leggings; invest in baby botox; use these tanning drops) with internal practices like breathwork, mindfulness, and journaling. These blurred lines between self-care and glow ups point to how commodified self-care has become—it is a hyper-individualistic practice that has been stripped of all its original meaning.

“In its essence, a glow up has always been a capitalistic, misogynistic practice. They have always been laden with Eurocentric beauty ideals that push us to be the thinnest, whitest, most feminine versions of ourselves.”

Self-care has radical, political roots. Historically, Black queer figures have consistently advocated for community care practices, like Angela Y. Davis, who once said: “(Practicing radical self-care) means we’re able to bring our entire selves into the movement, it means we incorporate into our work as activists ways of acknowledging and hopefully moving beyond trauma. It means a holistic approach.”

Audre Lorde popularised the term ‘self-care’ in her 1988 book A Burst of Light, describing it as a political act of self-preservation: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

Yet, in modern times, it is Black women who are so often excluded from self-care. Now, rich white women like Gwyneth Paltrow are seen as the leaders of it. Their version is devoid of activism, community, and politics—all of which are the base components of self-care. Self-care was meant to be a way for Black and marginalised communities to look after themselves in the face of white supremacy, but as it always does, white supremacy colonised it.

I am not trying to take your skincare or salt baths away from you, but it is important for all of us—myself included—to reflect on what self-care means. Yes, it’s important to carve out time to recuperate and look after ourselves, but it is also important to partake in collective care. To be part of a community and not fall into hyper-individualistic pursuits, which capitalism encourages.

Self-care can be a vital, powerful political tool, especially for women and marginalised people. But glowing up is not self-care. Glowing up is a temporary fix to feelings that only community and collective care can soothe. You can not filler, starve and smooth your way out of oppression.

I think that Angela Y. Davis quote might just change my life